- Home

- Rick Beyer

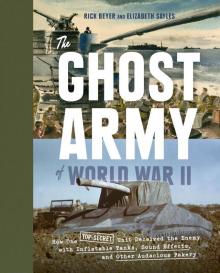

The Ghost Army of World War II Page 3

The Ghost Army of World War II Read online

Page 3

Making Dummy Land Mines and Paint Spray Equipment by George Vander Sluis, 1943

The tanks were manufactured by a consortium, including U.S. Rubber and other giants such as Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company as well as a collection of smaller companies, such as the L. R. Moulton Drapery Company in Melrose, Massachusetts, the Karl F. Jackson plant in Lowell, Massachusetts, and the Scranton Lace Curtain Manufacturing Company, in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

The first page of a United States Army “Catalog of Targets” listing the variety of dummies available for deception use during World War II, with details on weight and how many would fit into a truck

Theresa Ricard’s security badge at U.S. Rubber

U.S. Rubber temporarily shut down its work on barrage balloons and set up special annexes outside its giant Alice Mill building in Woonsocket in order to meet the deadline for getting the dummies to the Ghost Army. According to a company newsletter written at war’s end, “Speed was so essential that men and women were hired on Friday, the locations selected there were renovated Saturday and Sunday, and the decoy work was started the following Tuesday.” With the men headed off to war, it was mostly women who picked up the tools to get the job done. Newspaper ads invited women age sixteen to fifty to “help win the war” by working for the rubber company. One of those answering the call was a sixteen-year-old high school student named Theresa Ricard, who ended up gluing together dummy tanks after school for forty-nine cents an hour. “It stunk. And so did your clothes. When you come out of there, you strip, throw ’em in the washer.” She and other workers were told they were making targets. They had no idea until decades later that the dummies were used for quite a different purpose.

Barrage balloon, one of thousands manufactured by U.S. Rubber. These held aloft heavy cables used to keep enemy planes from attacking at low altitude.

The tanks were not simply giant balloons. They were built on a skeleton of inflatable rubber tubes, covered by rubberized canvas. This made them quicker to inflate and also insured that a single piece of shrapnel could not instantly deflate the entire tank. Ricard’s job was to work on the tubes that went into the turret. “We’d cement them and fold them different ways to make sure [they would] fit in the turret. We made sure one was long for the gun.”

Tanks were not the only inflatables constructed for the Ghost Army. Reporter Fred W. Dudley of the Lowell Sun later wrote that entering the Jackson plant in Lowell was like “walking into a fairyland as one sees jeeps, half tracks, three quarter ton truck…and innumerable other parts rising magically from heaps of rubbish-appearing material scattered about the floor.” Because of the time crunch, the men of the 603rd would not get to work with any of the dummies before they arrived in England. Until then, they had to carry out their training missions with handmade substitutes.

The unit selected for radio deception was the 244th Signal Company, commanded by Captain Irwin C. Vander Heide, who had been the chief switchman at the telephone office in Santa Monica, California. Unlike the 603rd, however, this unit did not join the Ghost Army intact. To handle the myriad challenges of radio deception, 40 percent of the unit was weeded out and replaced with more than one hundred skilled radio operators plucked from units around the country. The unit was renamed the Signal Company Special.

Inflatable half-track and artillery piece on the factory floor

Improvised dummy artillery piece

Stanley Nance and the jeep he named Kilowatt Kommand

One of those chosen was Sergeant Stanley Nance, a highly skilled telegrapher. Nance was a ukulele player and had learned strumming techniques that he transferred to the telegraph, giving him lightning-fast speed as an operator. He was on desert maneuvers with the Eleventh Armored Division when a stranger in a jeep came looking for him. “He said, ‘Get your equipment and come with me.’ And I said, ‘Where are you going?’ and he said, ‘All I can tell you is I’m not supposed to tell you anything, and for you to shut up.’” Lieutenant Bob Conrad, a signal officer for the Thirty-First Infantry Division, was another who found himself suddenly transferred to a mysterious new unit. He had no idea why he was there or what he was supposed to do, so he questioned a senior officer. That’s when he first learned about the dangerous aspects of serving in a unit designed to attract enemy attention, likely to be followed shortly by enemy fire. “He said: ‘Let’s put it this way, Lieutenant. If we are totally successful, you may not come back.’”

Sergeant Spike Berry, a college freshman who had worked part-time at a radio station in Minnesota, considered radio the stage setter. “When you think of the Twenty-Third Special Troops, you think of the inflatable tanks or the sound guys, and they’re great. But they have to have a stage on which to perform. And we provided that stage.”

German intelligence was highly dependent on radio interception to indicate what the enemy was doing. In North Africa the British had captured an entire German radio interception unit. Military historian Jonathan Gawne says they were stunned to learn how precisely the Germans could pinpoint where a unit was located by analyzing its radio traffic. By later estimates, German army units gathered as much as 75 percent of their intelligence from radio intercepts.

Ghost Army officers carefully studied the pattern of radio transmissions broadcast by the unit they were assigned to impersonate. Lieutenant Bob Conrad and other officers would “meet with the unit’s chief signal officer to learn specific call signs, techniques, et cetera practiced by that division.” That way, if they were simulating an infantry division moving across a given area, they would know how many times regimental headquarters would be likely to send messages to battalion headquarters, for example. They used this information to create realistic radio-deception scenarios. “It’s an art of knowing just how many and what type of messages to send,” says Gawne. Ghost Army radio operators would handle some of the division’s real radio traffic before the deception began, then keep operating as the real unit moved away, lending an extra degree of realism to their deception.

Much of the radio traffic took place via Morse code; the Germans were able to identify an individual operator by his style, or “fist,” as it was called. “When sending in code, an individual’s way of tapping his dots and dashes can be distinguished as clearly as his handwriting,” wrote Ralph Ingersoll, the Special Plans officer who helped coordinate the unit’s operations. So Ghost Army radio operators had to become mimics. The signal company trained its radio men to copy the precise techniques of the operators they were imitating, so that as the real radios went off the air and the fake ones took over, nobody would know the difference. “They came schooled in the styles and accents of every division due to be on the line,” wrote Ingersoll. “They had inventories of every real operator’s nicknames and peculiarities.” Stanley Nance recalled that he would study a radio operator for hours to learn his idiosyncrasies. To this day some experts claim that copying another operator’s fist is almost impossible. The fact is, however, that the Twenty-Third’s high-speed telegraphers did it routinely.

Officers of the 406th: from left, Lieutenant William Aliapoulos, Lieutenant John Kelper, Captain George Rebh, Lieutenant Thomas Robinson, and Lieutenant George Daley

In early January 1944 the commander of the 293rd Engineer Combat Battalion, taking part in desert maneuvers in Yuma, Arizona, received an order to detach his best company for a secret mission. He selected Company A, a crack unit commanded by recent West Point graduate Lieutenant George Rebh. Rebh was promoted to captain, and his unit became the 406th Engineer Combat Company Special.

The soldiers in the 406th had undergone two years of combat training, and Rebh thought their mission would likely involve demolition work in support of an infantry attack, a prospect that he looked forward to. “Being a regular army officer, you go to the sound of where the guns are firing.” He was disappointed to find out that was not the case, although he later came to believe that being in the Ghost Army was extremely beneficial to his army career.

The 406th wo

uld act as the unit’s security force—to be, as one of the men put it, “the only real soldiers in the unit.” At Camp Forrest they focused on physical fitness and combat training. As it turned out, once they were in the field they would find a role in the deception mission as well.

Nearly one thousand miles northeast of Camp Forrest, the sonic deception unit was formed and trained at the Army Experimental Station in upstate New York at Pine Camp (now Fort Drum). Using recorded sound to fool the enemy was a new strategy in World War II, made possible by technology that didn’t exist a few years earlier.

Captain Douglas Fairbanks Jr.

The military started experimenting with sonic deception in 1942. The United States Navy was the first to make operational use of the idea, thanks to actor-turned-naval-officer Douglas Fairbanks Jr. After observing British Commandos operations, Fairbanks was eager to form a navy deception team. The result was the Beach Jumpers program: small boats equipped with speakers and smoke machines used to create diversions during beach landings. Formed in 1943, the Beach Jumpers saw action in Italy.

The army followed suit, setting up its own sonic deception program under a colorful and charismatic officer named Hilton Howell Railey. Growing up in New Orleans, Railey had dreamed of becoming an actor but instead turned to journalism. After serving in the army during World War I, he went to Poland as a war correspondent. In the 1920s he helped organize Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s Antarctic expeditions and recruited Amelia Earhart to fly across the Atlantic—launching her to international fame. When Fortune magazine dispatched him to investigate the European arms industry, a Nazi agent tried (without success) to recruit him as Hitler’s PR man in America. In the late 1930s he wrote articles on military preparedness and penned a popular autobiography, Touched with Madness. A book reviewer for the New York Times wrote, “The author shows conclusively that he is again ready and capable of meeting fate on its own ground.” World War II would give him a chance.

His first job was to write a confidential report for the army on how to combat low morale among draftees. This led directly to the Why We Fight films, directed by Frank Capra, which explained to soldiers the reasons for America’s involvement in the war and the principles they were fighting for. Railey was then recalled to service as a colonel and put to work on sonic deception. Headstrong and debonair, he was the perfect person to handle the job. “He had style. He had grace,” recalled Lieutenant Dick Syracuse. “This guy was certainly a leader.” At Pine Camp, Railey went to work training two sonic units. The 3132 Signal Service Company Special served in the Ghost Army, while the 3133 operated independently in Italy.

Railey personally interviewed many of the officers chosen for the 3132, including Syracuse—a Bronx native who had been commanding an all-black chemical-warfare company training in the South. After he demanded equal privileges for his men, Syracuse suddenly found himself transferred and put on a train back north. He and Railey hit it off immediately. “I can remember so well his greeting to me was, ‘Lieutenant, the mission of your company will be to draw enemy fire.’ I suggested that as a kid from the Bronx, I certainly respect the role we have to play, but I reserve the right to kick a little ass myself if I get the opportunity. And he roared. He said, ‘I love it.’”

Another one who made the cut was Sergeant Jack McGlynn of Medford, Massachusetts. “I was interviewed for a top-secret organization, which was involved in psychological warfare and something to do with sound. I thought: sound—we were going to zap all the Germans; we’d end the war and that would be it. But it was more psychology than zapping.”

Members of the Sonic Company Special. Colonel Hilton Howell Railey is front row center, and Sergeant Jack McGlynn is third from the left in the back row.

Their mission was to simulate the sounds of troop movement and activity, especially at night, when enemy observation posts could hear but not see. The army considered using commercially available sound-effects recordings but decided that they would not offer adequate variety. An army report noted that trained observers could differentiate among types of tanks by the sound that they made, and could also determine a tank’s speed and whether it was going uphill or downhill. All these different sounds, and many more, needed to be recorded for use in different scenarios.

In early 1944 Railey sent a team with a portable audio studio down to the army proving ground at Fort Knox, Kentucky. An armored company of eighteen Sherman tanks and two hundred men rumbled around the maneuver grounds for three weeks to create the sound effects they would need. The area was closed off to all other activity, and planes were banned from flying over.

Ghost Army technicians worked side by side with experts from Bell Laboratories to record the sounds. A microphone with a burlap windscreen was set up on a tripod. In a van one hundred feet away, two soldiers manned turntables on which a recording head etched grooves into sixteen-inch transcription disks, the same kind used to make hit records. They captured the sounds of tanks, trucks, bulldozers, even the assembly of pontoon bridges used to ford rivers. “You could hear ’em hammering away and swearing,” marveled Private Harold Flinn. The Bell Labs engineers developed new techniques for recording sounds for deception purposes. For example, if a truck races past a microphone, the pitch of the sound will drop, due to a scientific principle known as the Doppler effect. That could be a dead giveaway to an enemy observer, since that effect would not normally be heard from far away. To avoid this telltale change in pitch, they came up with the clever idea of locating a microphone at the center of a circle of continuously moving vehicles, so that sounds were recorded free of the Doppler effect.

Uncovering the speakers on a sonic half-track

Various sounds could be cued up on different turntables and mixed together to create whatever scenario was required—one of the earliest known uses of multitrack recording. These mixes were then recorded on a wire recorder—a predecessor to the tape recorder that was advanced technology in the early 1940s. A single spool contained two miles of magnetized wire, enough for thirty minutes of sound; unlike a record, it would never skip.

The recordings were played over five-hundred-pound speakers mounted on half-tracks. On the back of his half-track, recalled Corporal Al Albrecht, “was the biggest boom box you ever saw. But it played sounds of tanks and activity.” To evaluate different speaker systems, the Army turned to Harvard University’s Electro-Acoustic Laboratory, run by a young scientist named Leo Beranek. “Because of the intense sound levels that such powerful systems had to produce,” wrote Beranek, “they could not conveniently be tested outdoors.” Instead, Beranek built a sound-deadening chamber that would hide the testing from the public. The result became known as Beranek’s Box. It was a room with no echo at all, one of the first ever constructed. Beranek even coined a new word to describe it, calling it an “anechoic” chamber. The forty-by-fifty-foot room, nearly four stories in height, was lined with nineteen thousand fiberglass wedges—nine boxcars’ worth. “This meant that you had a room that was almost perfectly quiet. You couldn’t hear any noise from outside, and you could hear the blood rushing in your ear, which was a new experience.” Beranek eventually became one of the founders of the legendary high-tech company Bolt, Beranek and Newman (now BBN Technologies), which did much of the early engineering work on the Internet. Over the years, thousands of anechoic chambers have been built for audio testing, most using the wedge design pioneered by Beranek and inspired by the Ghost Army.

Mobile weather station

No detail was overlooked. Wind speed and direction had to be factored in to each deception, so the army created a mobile weather station to go into action with the sonic unit. Bell Labs put together firing tables—charts similar to those used by the artillery—to determine how loud to project the sound, depending on the weather, the terrain, and the distance of the enemy.

Leo Beranek (right) in the anechoic chamber that became known as Beranek’s Box

The result of all this technology and effort was remarkable. Clare Beck,

an officer who worked with Harris and Ingersoll in the Special Plans branch in London, returned to the United States to assess the development of sonic deception and came away impressed. “The sonic equipment I observed is excellent and practical,” he wrote in his report. “The max range is 7000 yards for motor convoy sounds and bridge building activities, and approximately four thousand yards for sounds of tanks. The sound is projected with deceptive fidelity, and in my opinion and the opinion of others is so near like the real sound as to be impossible to distinguish from it.”

Of course, any technology is only as good as the men who operate it, and Railey felt he was sending to Europe a team of the very best, as he expressed in a letter to the father of Sergeant John Borders. “John is a member of a pioneer unit which is unique in the Army of the United States. Never anywhere in my command experience—in three wars—have I known finer men. I claim them for my very own.”

Military Transport by Joseph Mack

The three-month training period went by in a flash. In April 1944, the camouflage, radio, and combat engineering units at Camp Forrest boarded a New York-bound train to start their journey to England. The 3132 sonic unit would join them later in Europe. Private Irving Stempel was one of many who wondered if they could really fool the Germans. “You couldn’t really believe that what we were going to do would be effective. How could we come along with rubber dummies and blow [them] up and make it look real?“While some cracked wise about the crazier aspects of their mission, others were quietly convinced they were going to play a vital role in the war effort.

The Ghost Army of World War II

The Ghost Army of World War II The Greatest War Stories Never Told

The Greatest War Stories Never Told