- Home

- Rick Beyer

The Ghost Army of World War II Page 2

The Ghost Army of World War II Read online

Page 2

The 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion Special

This was the largest unit in the Ghost Army, with 379 men. These visual deceivers, also known as camoufleurs, used an array of inflatable rubber tanks, trucks, artillery, and jeeps to create deceptive tableaux for enemy aerial reconnaissance or distant observers. The unit had spent the previous two years doing camouflage work and included in its ranks many artists specially recruited for that job.

The Signal Company Special

Formerly the 244th Signal Company, this group of 296 men carried out radio deception, also called “spoof radio.” Operators created phony traffic nets, impersonating radio operators from real units. They mastered the art of mimicking an operator’s method of sending Morse code, to prevent the enemy from realizing that the real unit and its radio operator were long gone.

The 3132 Signal Service Company Special

This sonic deception unit was staffed with 145 men. Their mission was to play sound effects from powerful speakers mounted on half-tracks (armored vehicles with wheels in the front and tracks in the back), to simulate the sounds of units moving and operating at night. Recently formed, they had been undergoing training at the Army Experimental Station at Pine Camp (now Fort Drum) in upstate New York when the Twenty-Third was assembled and would join them later in England.

The 406th Engineer Combat Company Special

Led by Captain George Rebh, the 168 men of the 406th were trained as fighting soldiers. They provided perimeter security for the rest of the Ghost Army. They also executed construction and demolition tasks, including digging tank and artillery positions. The men of the 406th frequently used their bulldozers to simulate tank tracks as part of the visual deception.

A whimsical diagram of the Twenty-Third Headquarters Special Troops by Fred Fox, who served in the unit and wrote its official army history

This operations map was designed by Corporal George Martin, with help from some of his fellow soldiers. After he returned to the United States, Martin had copies printed and distributed to each of the men, as a memento of their wartime adventure.

These four units, plus a headquarters company—eleven hundred men in all—were capable of simulating two divisions—approximately thirty thousand men—to confuse and confound the enemy. The Twenty-Third eventually came under the direct command of General Omar Bradley’s Twelfth United States Army Group, carrying out operations planned by Bradley’s Special Plans Branch—under Billy Harris and Ralph Ingersoll.

The biggest of the four units brought together for the deception mission was the 603rd Camouflage Engineers. It was an unusual unit, rumored to have the highest average IQ of any unit in the army. But what really made it unique was that it was loaded with some of the most unmilitary people imaginable—artists.

Detail of operations map

New York University students studying camouflage in 1943

THE ART BOYS

We were looked on as kind of nutcases by the hardworking, no-nonsense backbone of America, the people that worked for a living and didn’t sketch.

— Jack Masey

Private Ned Harris was only eighteen years old when he reported for duty at Fort Meade, Maryland, in 1942. He was there to join up with the newly formed 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion Special. Young and nervous, far from home, he had no idea what to expect. As he signed in, someone asked him where he was from, and he answered, “New York.” Then another soldier inquired if he had attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

New Recruit by Walter Arnett, 1942

“I immediately said yes,” recalled Harris, “and they began laughing. I didn’t know whether to be embarrassed or what. Were they laughing with me or at me?” Then another voice chimed in with words that made Harris feel right at home. “Just another artist arrived to be part of our fraternity.” Harris was one of many creative types who had found their way into the 603rd. Many others also came from Pratt. James Boudreau, the dean of Pratt’s art school, was a general in the United States Army reserve. In the early 1940s, with war already raging in Europe and Asia and fears rising over the threat of aerial devastation from enemy bombing, the farsighted Boudreau organized an experimental laboratory dedicated to camouflage research and development. He recruited camouflage experts to the faculty and instituted a camouflage course.

Bob Tompkins was quick to sign up for it. He was taking courses at Pratt while also working at an advertising agency in the Chrysler Building for $17.50 a week. Ed Biow, Ellsworth Kelly, George Martin, and William Sayles also took the course. They built detailed tabletop models and went out to the Pratt family estate on the North Shore of Long Island to work with camouflage netting. Boudreau, a pilot, would fly overhead and snap photos to show them what their camouflage installations looked like from the air. “Amateuring around,” Biow called it, but it led them all into the 603rd.

Ray Harford, Bob Boyajian, and Victor Dowd (left to right, seated and looking at camera) illustrating comics at Jack Binder’s studio in 1940. They later served together in the Ghost Army.

Kelly’s journey to the unit involved an unusual detour. He requested assignment to the 603rd, but when his orders didn’t come through, he was transferred to Camp Hale, Colorado, to join the Tenth Mountain Division ski troops. This, in spite of the fact he had never been on skis in his life! When his orders to join the camouflage unit finally arrived, he felt sorry to leave the beautiful mountain camp.

Victor Dowd recalled that Dean Boudreau actively recruited art students (and recent graduates) for newly organized army camouflage battalions. Dowd had known since childhood that he was going to be an artist. “My mother never had to worry about me on rainy days, because I’d occupy myself by drawing.” After graduating from Pratt in 1940, he and classmates Ray Harford and Bob Boyajian worked together as comic-strip artists at Jack Binder’s studio during what is now considered the golden age of comics. They drew such heroes as Bulletman, Captain Midnight, and Spy Smasher. Under the auspices of Boudreau, all three found their way into the 603rd.

Comic book buddies Ray Harford, Bob Boyajian (with bazooka), and Victor Dowd training at Fort Meade, 1943

As did Arthur Shilstone. Unlike Victor Dowd, Shilstone had no intention of being an artist. “I thought the thing to do was to be a businessman, wear a blue suit, someday have the end office.” So he took a lot of business courses, in which he did quite poorly. But he excelled in an art course. His art teacher suggested he should think about a career in art. He dutifully went back to his business teachers to see what they thought. He recalled with laughter how enthusiastic they were. “They said, ‘That’s a great idea, Arthur. You really should go and do something else.’” So he went to Pratt to study illustration and ended up in the 603rd.

John Jarvie was studying at New York’s Cooper Union when he enlisted. “It was a big war,” recalled Jarvie, “and everybody went.” Jarvie heard about the camouflage unit and applied to be a part of it. “You had to write to them, and they had to accept you—it had nothing to do with the army draft at all.” Seventeen-year-old freshman Art Kane and twenty-five-year-old graduate Arthur Singer also hailed from Cooper Union. Jack Masey was a recent graduate from the New York High School of Music and Art. Keith Williams was a prizewinning artist in his mid-thirties. Bernie Mason was designing display windows for a store in Philadelphia. Harold Laynor was a recent graduate of the Parsons School of Design, also in New York City. George Vander Sluis had painted post office murals for the WPA and taught art at the Broadmoor Academy in Colorado. Bill Blass was a fledgling fashion designer who had recently moved to New York from Fort Wayne, Indiana. They and many other artists filled the ranks of the 603rd.

Ray Harford by Victor Dowd, 1945

Victor Dowd’s sketchbook, 1944

Self-Portrait by Arthur Singer, 1944

Camouflage lesson

A report handwritten by Bill Blass about the merits of using chicken feathers for camouflage

Ellsworth Kelly with silk screens, Fort Meade, 1943

PHOTO COURTESY OF ELLSWORTH KELLY

After basic training at Fort Meade, they began learning the ins and outs of camouflage. They experimented with everything from tin cans to chicken feathers to see what they would look like to aerial observers. They studied how to use texture, color, shadow, blending, and shape in camouflage. Ellsworth Kelly helped to silk-screen posters that introduced infantry units to these basic camouflage principles. In later years Kelly was to become famous for his minimalist painting and sculpture, and art critic Eugene Goossen argued that this exposure to military camouflage helped shape Kelly’s aesthetic. “The involvement with form and shadow, with the construction and destruction of the visible … was to affect nearly everything he did in painting and sculpture.”

Soon they graduated to larger-scale projects. Fearing German bomber raids, the army had the unit camouflage coastal defense artillery on Long Island and at the Glenn L. Martin plant in Baltimore, where B-26 bombers were made. “Our outfit was responsible for disguising that and covering it,” recalled Ned Harris, “so from the air it looked like it was the countryside.” In 1943 they took part in large-scale maneuvers in Tennessee.

Camouflaged Glenn L. Martin plant, Baltimore

Quick Nap by Tony Young, 1944

Watercolor by John Hapgood, 1944

Portrait by George Martin, 1945

GI Sketching by Joseph Mack, 1943

But while camouflage was their job, art was their love. The 603rd served as an incubator in which artists could hone their skills. “I learned more about who I was as an artist and…my craft by being there rather than even at school,” said Harris, “and it continued till the end.”

The artists in the 603rd sketched and painted all sorts of things: their barracks, their buddies, themselves. “It isn’t as though we weren’t busy,” said Victor Dowd. “But you have to realize, no matter how busy a soldier is, there’s always down time. Soldiers are playing cards, they’re shooting craps, they’re reading. And I drew. I just developed the habit, and I don’t think it’s ever left me.” Harold Laynor recalled his first sergeant “was always berating me for taking so much time up with my, as he called it, ‘darn painting.’” Laynor thought the sergeant should have expected no different, given that the men were “a mass of artists and architects” who thought they “were going to camouflage the United States.”

Not all the soldiers in the 603rd were artists. There were policemen, farmers, accountants, shoe salesmen, and other people from all walks of life. “It was a wild array of all kinds of people,” said Arthur Shilstone. For Jack Masey, a kid from Brooklyn, it was an eye-opening experience. “I’d only known Brooklynites or Manhattanites. Now suddenly I was thrown into another world. I was intrigued by the people who constituted this world, their accents, the obscenities they threw out. This was another awakening for me: hey, this is America. It’s got all kinds of crazy people in it.”

The sharp cultural divide in the unit was obvious to many. Bill Blass marveled that he could hear Beethoven’s Fifth at one end of the barracks and “Pistol Packin’ Mama” at the other. “And we were looked on as kind of nutcases,” said Jack Masey, “by the hardworking, no-nonsense backbone of America, the people that worked for a living and didn’t sketch.”

Some even thought that the young artists wouldn’t be able to hack the army. Not so. “The artists did what everybody else did,” said Arthur Shilstone. “They made the hikes and [carried] their rifles and everything else, and they were as good or better than the other guys: the bartenders, the truck drivers, and so forth.” In early 1943 Private Harold Dahl, a young sculptor from New Jersey, noted in a letter to his mother that of the twenty sergeants in his company, fifteen were artists. “And some of these tough engineers thought the art boys would be flops!” he added with pride.

In the end, as in countless other army units, the young men of different backgrounds found a way to put aside their differences and work together. “It did pit us against people who probably never knew or met an artist,” said Ned Harris, “and knew nothing about the world that was ours. And they learned something from us, and we learned from them.”

The 603rd had been together for nearly two years when it was uprooted from Fort Meade in January 1944 and sent to Camp Forrest in Tennessee to be part of the Twenty-Third Headquarters Special Troops. Instead of trying to hide things, they were now going to be in the risky business of drawing attention to themselves. Lieutenant Gil Seltzer, a twenty-nine-year-old New York City architect, concluded that the 603rd was being attached to a “suicide outfit.” But Private Dahl, for one, found the new assignment very much to his taste. He wrote home to say that he couldn’t talk about what they were going to do, “but it promises to be very interesting and frankly it looks like we are at last going to play a real part in the war effort.”

Caricatures of Tony Young, Max David, and James Steg by Jack Masey, 1944

Inflatable M-4 Sherman tank

MEN OF WILE

You couldn’t really believe that what we were going to do would be effective. How could we come along with rubber dummies and blow [them] up and make it look real?

— Irving Stempel

Officers who had once commanded 32-ton tanks, felt frustrated and helpless with a battalion of rubber M-4s, 93 pounds fully inflated. The adjustment from man of action to man of wile was most difficult. Few realized at first that one could spend just as much energy pretending to fight as actually fighting.

— Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops

The clock was running as the Twenty-Third Headquarters Special Troops began to take shape in January 1944. Everyone knew that the invasion of Europe was only a matter of months away. They had precious little time during which to get organized and learn their deception mission. The United States Army had no doctrine for tactical deception, no book for them to go by. They would have to develop much of their own training, tactics, techniques, and procedures, and teach themselves to be deceivers.

Colonel Harry L. Reeder, commander of the Twenty-Third Headquarters Special Troops

The commander of the unit, Colonel Harry L. Reeder, was an old-school infantry officer who had been serving since World War I. Colonel Billy Harris and Captain Ralph Ingersoll, in the Special Plans branch, thought him a poor choice because of his lack of flexibility and receptivity to new ideas. Harris derided Reeder as “an old fud.” Reeder, by all accounts, was none too happy with his assignment, either. On at least one occasion he suggested to the War Department that the Twenty-Third should be dissolved, freeing him up to command an infantry regiment. Many of the men who served under him came to regard Reeder as a narrow-minded military man uninterested in adapting to the unusual needs of a deception unit.

Lieutenant Colonel Clifford Simenson, the unit’s operations officer, was cut from a different cloth. A protégé of one of the army’s highest- ranking and best-regarded officers, General Leslie McNair, Simenson, too, had hoped for an infantry command. Upon being assigned to the Twenty-Third, he initially found himself perplexed about how best to proceed. “There were no manuals, no instructions, no guidance, and no orders from higher headquarters except to prepare for overseas movement.” Unlike Reeder, however, Simenson threw himself wholeheartedly into the deception mission. Intelligent and open-minded, he was instrumental in formulating the doctrines and tactics they would employ on the battlefield to simulate larger units under a variety of different conditions.

Surprisingly, for such a small unit, there were a number of other lieutenant colonels and majors, many of them West Pointers, on the headquarters staff. They were there to provide expertise from infantry, artillery, armored, and other branches of the military that would be needed to plan and carry out convincing deceptions.

Three of the four units that made up the Ghost Army reported to Colonel Reeder at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, while the sonic deception unit was organized and trained at the Army Experimental Station, located at Pine Camp in upstate New York. A huge amo

unt of work had to be undertaken in a short time to prepare the various branches of the Ghost Army for action in Europe—not only in the two army camps but also in factories, labs, and testing facilities across the country.

Ellsworth Kelly and an improvised dummy jeep

PHOTO COURTESY OF ELLSWORTH KELLY

Soldiers in the 603rd assembling an improvised wooden dummy

The Twenty-Third’s largest unit, the 603rd Camouflage Engineers, arrived at Camp Forrest in late January 1944. They did not yet have decoys to work with, so they improvised, fabricating dummy tanks out of wood and burlap and learning how to use them to create convincing deceptions that would fool enemy air reconnaissance. They used a spotter plane to evaluate what they had created and learn how to make things more realistic.

Meanwhile, a mad dash was underway to produce dummies. After conducting tests in the California desert, the army had settled on using inflatables. Many of them were designed by Fred Patten, development director of the U.S. Rubber Company plant in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Patten had also designed the inflatable one-man life rafts carried by fighter pilots in the Pacific.

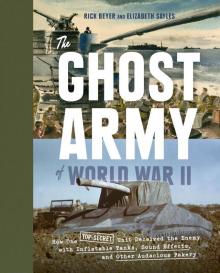

The Ghost Army of World War II

The Ghost Army of World War II The Greatest War Stories Never Told

The Greatest War Stories Never Told